Creative Thinking

The Origin of Human Imagination: From Neuroscience to Creative Marketing

By Taylor Holland on January 8, 2015

What do Fitbits, cave paintings, The Hunger Games, democracy, and the most creative marketing campaigns of 2014 have in common? They are all products of someone's imagination.

Each of history's greatest business and creative outputs began as a mere ember in somebody's mind-a glowing vision of something that didn't exist, but that could. These ideas were then nurtured into innovative solutions, medical breakthroughs, works of art, and other game changers. But what led to that initial ember? What do we know about the human brain and the origination of ideas, and what do we still have to learn?

The Elusive Creative Process

For centuries, scientists have attempted to explain what has previously been considered an unobservable phenomenon: the human imagination. But recent discoveries and new technology are providing fresh data about how our brains behave during the creative process, how we dream up new ideas, and why some people are more creative than others.

Some early theories about the science of creativity have proven to be true. For example, creativity does seem to be hereditary, and highly creative people are more likely to struggle with drug abuse and psychological disorders (hence the term "mad genius").

Other long-held beliefs about the origins of imagination have been disproven in recent years, including when it actually originated. As Ferris Jabr writes in the New York Times Magazine article, "Hunting for the Origins of Symbolic Thought":

"Homo sapiens began to emigrate from Africa between 60,000 and 125,000 years ago, but did not reach Europe until about 40,000 years ago. It was only there, concluded 20th-century archaeologists, that humans began to think symbolically, to make simple figurines and geometric designs and, eventually, paintings. How else to explain the abundance of Paleolithic art in Europe and the comparatively sparse Stone Age galleries of Africa and Asia?"

But recent discoveries have proven that even our early ancestors had the capacity for creativity.

During a 2011 expedition to the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, archaeologists found a 39,000-year-old hand stencil and a 354,000-year-old cave painting-one of the oldest known examples of figurative art. And in 1991, during a dig in South Africa's Blombos Cave, researchers discovered a 100,000-year-old paintbrush made of animal bone and 75,000-year-old geometric engravings.

Surviving in the wild and fending off prehistoric predators might have prevented early man from having much arts-and-crafts time, and centuries of weather damage erased many of their creations before they could be safely archived in museums. But the Stone Age wasn't exactly the dark age we've assumed it was. The human brain already knew how to think outside the box-when it had the luxury to do so.

This Is Your Brain on Creativity

There's a lot we still don't know about how the brain generates new ideas. Brain mapping is in its infancy, and creativity is hard enough to define, never mind objectively study. How do you identify "creative" subjects? How do you see creativity on a brain scan? And how creative can you really expect people to be on demand, while sitting completely still in an MRI machine?

Despite these challenges, several leading neuroscientists have made significant headway in this new area of study, giving us early insight into what's happening in our heads as we imagine and disrupting old theories about what makes a person creative.

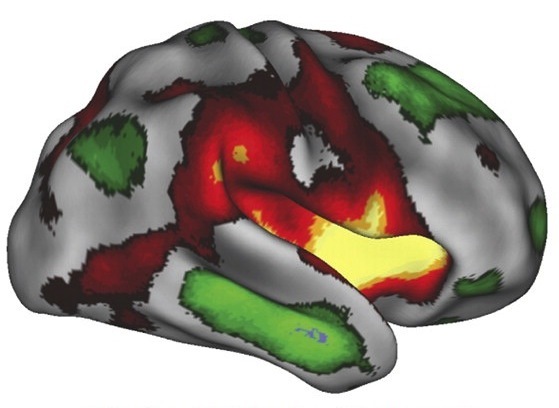

Most notably, there's the concept that a person is either "left-brained" (translation: an analytical, literal-minded bore) or "right-brained" (a creative, artsy flake). Turns out, the creative process requires both sides of the brain, working in tandem. More specifically, it involves three large-scale brain networks:

- The Executive Attention Network is used for tasks that require intense focus, such as concentrating on a challenging lecture or solving complex problems.

- The Imagination Network, or the Default Network, is called on when we imagine situations based on personal experiences, such as when we remember something that happened in the past, think about the future, or consider alternative scenarios to the present. The Imagination Network also comes into play when we try to consider what someone else is thinking.

- The Salience Network constantly monitors both external events and our internal thoughts, tapping into whatever information is most salient to solving the task at hand. This network is important for dynamically switching between networks.

(Green = The Executive Attention Network; Red = The Imagination Network; Yellow = The Salience Network)

Photo Source: National Academy of Sciences

None of these key creativity networks are located exclusively on the left or right side of the brain. Imagining, innovating, and creating requires the entire mind. These tasks also require both creative and analytical skills. What value does a good idea have without the analytical skills to hone it and eventually bring it to life? Likewise, even the best analytical skills won't help you solve a problem unless you can imagine a way to put that information to good use.

Put a Little Science in Your Art

What does all this mean for content marketers, outside of giving us new terminology to discuss creativity? Not a whole lot just yet. But as scientists continue to study the human brain - the most complex computer that exists - we'll learn more about the science behind art, how to boost our creativity and make connections we didn't see before, and how to engage the creativity of others with our marketing. And that's powerful information to have.

To learn about creative marketing tactics that will engage your audience, subscribe to Content Standard updates.